Full-text search is everywhere. From finding a book on Scribd, a movie on Netflix, toilet paper on Amazon, or anything else on the web through Google (like how to do your job as a software engineer), you’ve searched vast amounts of unstructured data multiple times today. What’s even more amazing, is that you’ve even though you searched millions (or billions) of records, you got a response in milliseconds. In this post, we are going to explore the basic components of a full-text search engine, and use them to build one that can search across millions of documents and rank them according to their relevance in milliseconds, in less than 150 lines of Python code!

Data

All the code you in this blog post can be found on Github. I’ll provide links with the code snippets here, so you can try running this yourself. You can run the full example by installing the requirements (pip install -r requirements.txt) and run python run.py. This will download all the data and execute the example query with and without rankings.

Before we’re jumping into building a search engine, we first need some full-text, unstructured data to search. We are going to be searching abstracts of articles from the English Wikipedia, which is currently a gzipped XML file of about 785mb and contains about 6.27 million abstracts1. I’ve written a simple function to download the gzipped XML, but you can also just manually download the file.

Data preparation

The file is one large XML file that contains all abstracts. One abstract in this file is contained by a <doc> element, and looks roughly like this (I’ve omitted elements we’re not interested in):

<doc>

<title>Wikipedia: London Beer Flood</title>

<url>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Beer_Flood</url>

<abstract>The London Beer Flood was an accident at Meux & Co's Horse Shoe Brewery, London, on 17 October 1814. It took place when one of the wooden vats of fermenting porter burst.</abstract>

...

</doc>

The bits were interested in are the title, the url and the abstract text itself. We’ll represent documents with a Python dataclass for convenient data access. We’ll add a property that concatenates the title and the contents of the abstract. You can find the code here.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Abstract:

"""Wikipedia abstract"""

ID: int

title: str

abstract: str

url: str

@property

def fulltext(self):

return ' '.join([self.title, self.abstract])

Then, we’ll want to extract the abstracts data from the XML and parse it so we can create instances of our Abstract object. We are going to stream through the gzipped XML without loading the entire file into memory first2. We’ll assign each document an ID in order of loading (ie the first document will have ID=1, the second one will have ID=2, etcetera). You can find the code here.

import gzip

from lxml import etree

from search.documents import Abstract

def load_documents():

# open a filehandle to the gzipped Wikipedia dump

with gzip.open('data/enwiki.latest-abstract.xml.gz', 'rb') as f:

doc_id = 1

# iterparse will yield the entire `doc` element once it finds the

# closing `</doc>` tag

for _, element in etree.iterparse(f, events=('end',), tag='doc'):

title = element.findtext('./title')

url = element.findtext('./url')

abstract = element.findtext('./abstract')

yield Abstract(ID=doc_id, title=title, url=url, abstract=abstract)

doc_id += 1

# the `element.clear()` call will explicitly free up the memory

# used to store the element

element.clear()

Indexing

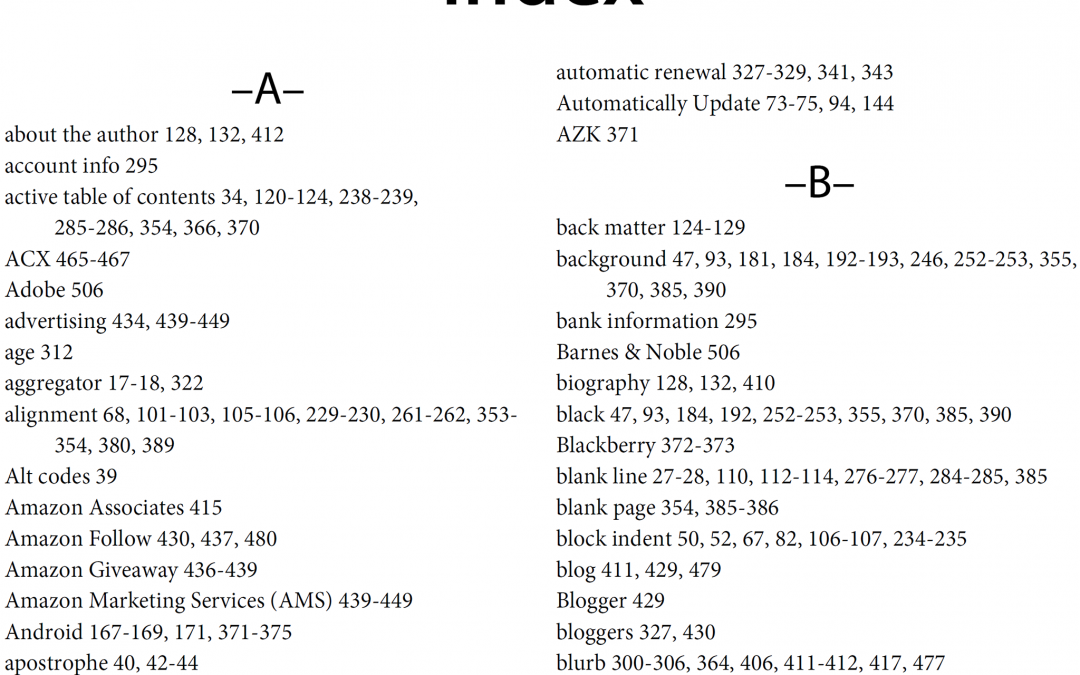

We are going to store this in a data structure known as an “inverted index” or a “postings list”. Think of it as the index in the back of a book that has an alphabetized list of relevant words and concepts, and on what page number a reader can find them.

Practically, what this means is that we’re going to create a dictionary where we map all the words in our corpus to the IDs of the documents they occur in. That will look something like this:

{

...

"london": [5245250, 2623812, 133455, 3672401, ...],

"beer": [1921376, 4411744, 684389, 2019685, ...],

"flood": [3772355, 2895814, 3461065, 5132238, ...],

...

}

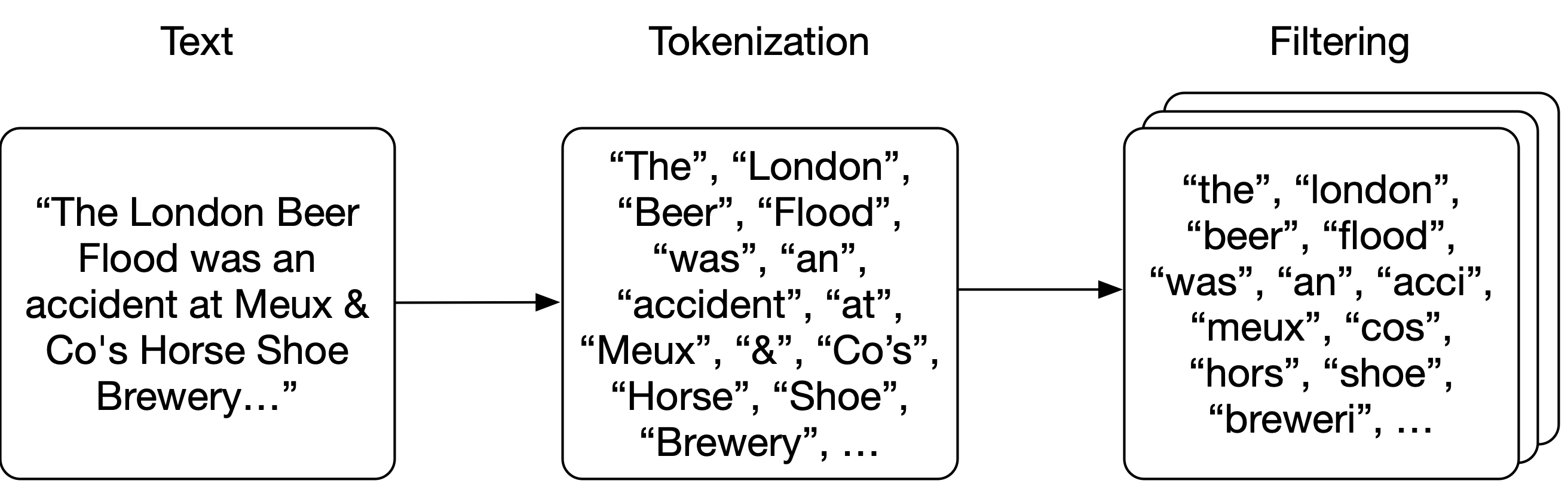

Note that in the example above the words in the dictionary are lowercased; before building the index we are going to break down or analyze the raw text into a list of words or tokens. The idea is that we first break up or tokenize the text into words, and then apply zero or more filters (such as lowercasing or stemming) on each token to improve the odds of matching queries to text.

Analysis

We are going to apply very simple tokenization, by just splitting the text on whitespace. Then, we are going to apply a couple of filters on each of the tokens: we are going to lowercase each token, remove any punctuation, remove the 25 most common words in the English language (and the word “wikipedia” because it occurs in every title in every abstract) and apply stemming to every word (ensuring that different forms of a word map to the same stem, like brewery and breweries3).

The tokenization and lowercase filter are very simple:

import Stemmer

STEMMER = Stemmer.Stemmer('english')

def tokenize(text):

return text.split()

def lowercase_filter(tokens):

return [token.lower() for token in tokens]

def stem_filter(tokens):

return STEMMER.stemWords(tokens)

Punctuation is nothing more than a regular expression on the set of punctuation:

import re

import string

PUNCTUATION = re.compile('[%s]' % re.escape(string.punctuation))

def punctuation_filter(tokens):

return [PUNCTUATION.sub('', token) for token in tokens]

Stopwords are words that are very common and we would expect to occcur in (almost) every document in the corpus. As such, they won’t contribute much when we search for them (i.e. (almost) every document will match when we search for those terms) and will just take up space, so we will filter them out at index time. The Wikipedia abstract corpus includes the word “Wikipedia” in every title, so we’ll add that word to the stopword list as well. We drop the 25 most common words in English.

# top 25 most common words in English and "wikipedia":

# https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Most_common_words_in_English

STOPWORDS = set(['the', 'be', 'to', 'of', 'and', 'a', 'in', 'that', 'have',

'I', 'it', 'for', 'not', 'on', 'with', 'he', 'as', 'you',

'do', 'at', 'this', 'but', 'his', 'by', 'from', 'wikipedia'])

def stopword_filter(tokens):

return [token for token in tokens if token not in STOPWORDS]

Bringing all these filters together, we’ll construct an analyze function that will operate on the text in each abstract; it will tokenize the text into individual words (or rather, tokens), and then apply each filter in succession to the list of tokens. The order is important, because we use a non-stemmed list of stopwords, so we should apply the stopword_filter before the stem_filter.

def analyze(text):

tokens = tokenize(text)

tokens = lowercase_filter(tokens)

tokens = punctuation_filter(tokens)

tokens = stopword_filter(tokens)

tokens = stem_filter(tokens)

return [token for token in tokens if token]

Indexing the corpus

We’ll create an Index class that will store the index and the documents. The documents dictionary stores the dataclasses by ID, and the index keys will be the tokens, with the values being the document IDs the token occurs in:

class Index:

def __init__(self):

self.index = {}

self.documents = {}

def index_document(self, document):

if document.ID not in self.documents:

self.documents[document.ID] = document

for token in analyze(document.fulltext):

if token not in self.index:

self.index[token] = set()

self.index[token].add(document.ID)

Searching

Now we have all tokens indexed, searching for a query becomes a matter of analyzing the query text with the same analyzer as we applied to the documents; this way we’ll end up with tokens that should match the tokens we have in the index. For each token, we’ll do a lookup in the dictionary, finding the document IDs that the token occurs in. We do this for every token, and then find the IDs of documents in all these sets (i.e. for a document to match the query, it needs to contain all the tokens in the query). We will then take the resulting list of document IDs, and fetch the actual data from our documents store4.

def _results(self, analyzed_query):

return [self.index.get(token, set()) for token in analyzed_query]

def search(self, query):

"""

Boolean search; this will return documents that contain all words from the

query, but not rank them (sets are fast, but unordered).

"""

analyzed_query = analyze(query)

results = self._results(analyzed_query)

documents = [self.documents[doc_id] for doc_id in set.intersection(*results)]

return documents

In [1]: index.search('London Beer Flood')

search took 0.16307830810546875 milliseconds

Out[1]:

[Abstract(ID=1501027, title='Wikipedia: Horse Shoe Brewery', abstract='The Horse Shoe Brewery was an English brewery in the City of Westminster that was established in 1764 and became a major producer of porter, from 1809 as Henry Meux & Co. It was the site of the London Beer Flood in 1814, which killed eight people after a porter vat burst.', url='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horse_Shoe_Brewery'),

Abstract(ID=1828015, title='Wikipedia: London Beer Flood', abstract="The London Beer Flood was an accident at Meux & Co's Horse Shoe Brewery, London, on 17 October 1814. It took place when one of the wooden vats of fermenting porter burst.", url='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Beer_Flood')]

Now, this will make our queries very precise, especially for long query strings (the more tokens our query contains, the less likely it’ll be that there will be a document that has all of these tokens). We could optimize our search function for recall rather than precision by allowing users to specify that only one occurrence of a token is enough to match our query:

def search(self, query, search_type='AND'):

"""

Still boolean search; this will return documents that contain either all words

from the query or just one of them, depending on the search_type specified.

We are still not ranking the results (sets are fast, but unordered).

"""

if search_type not in ('AND', 'OR'):

return []

analyzed_query = analyze(query)

results = self._results(analyzed_query)

if search_type == 'AND':

# all tokens must be in the document

documents = [self.documents[doc_id] for doc_id in set.intersection(*results)]

if search_type == 'OR':

# only one token has to be in the document

documents = [self.documents[doc_id] for doc_id in set.union(*results)]

return documents

In [2]: index.search('London Beer Flood', search_type='OR')

search took 0.02816295623779297 seconds

Out[2]:

[Abstract(ID=5505026, title='Wikipedia: Addie Pryor', abstract='| birth_place = London, England', url='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Addie_Pryor'),

Abstract(ID=1572868, title='Wikipedia: Tim Steward', abstract='|birth_place = London, United Kingdom', url='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tim_Steward'),

Abstract(ID=5111814, title='Wikipedia: 1877 Birthday Honours', abstract='The 1877 Birthday Honours were appointments by Queen Victoria to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of the British Empire. The appointments were made to celebrate the official birthday of the Queen, and were published in The London Gazette on 30 May and 2 June 1877.', url='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1877_Birthday_Honours'),

...

In [3]: len(index.search('London Beer Flood', search_type='OR'))

search took 0.029065370559692383 seconds

Out[3]: 49627

Relevancy

We have implemented a pretty quick search engine with just some basic Python, but there’s one aspect that’s obviously missing from our little engine, and that’s the idea of relevance. Right now we just return an unordered list of documents, and we leave it up to the user to figure out which of those (s)he is actually interested in. Especially for large result sets, that is painful or just impossible (in our OR example, there are almost 50,000 results).

This is where the idea of relevancy comes in; what if we could assign each document a score that would indicate how well it matches the query, and just order by that score? A naive and simple way of assigning a score to a document for a given query is to just count how often that document mentions that particular word. After all, the more that document mentions that term, the more likely it is that it is about our query!

Term frequency

Let’s expand our Abstract dataclass to compute and store it’s term frequencies when we index it. That way, we’ll have easy access to those numbers when we want to rank our unordered list of documents:

# in documents.py

from collections import Counter

from .analysis import analyze

@dataclass

class Abstract:

# snip

def analyze(self):

# Counter will create a dictionary counting the unique values in an array:

# {'london': 12, 'beer': 3, ...}

self.term_frequencies = Counter(analyze(self.fulltext))

def term_frequency(self, term):

return self.term_frequencies.get(term, 0)

We need to make sure to generate these frequency counts when we index our data:

# in index.py we add `document.analyze()

def index_document(self, document):

if document.ID not in self.documents:

self.documents[document.ID] = document

document.analyze()

We’ll modify our search function so we can apply a ranking to the documents in our result set. We’ll fetch the documents using the same Boolean query from the index and document store, and then we’ll for every document in that result set, we’ll simply sum up how often each term occurs in that document

def search(self, query, search_type='AND', rank=True):

# snip

if rank:

return self.rank(analyzed_query, documents)

return documents

def rank(self, analyzed_query, documents):

results = []

if not documents:

return results

for document in documents:

score = sum([document.term_frequency(token) for token in analyzed_query])

results.append((document, score))

return sorted(results, key=lambda doc: doc[1], reverse=True)

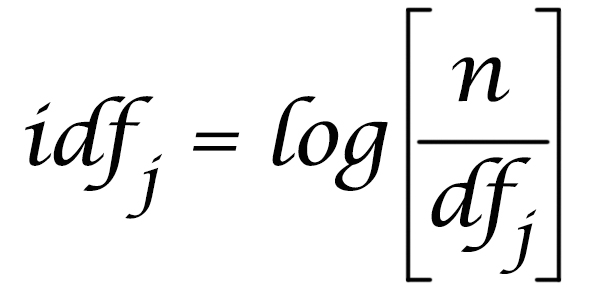

Inverse Document Frequency

That’s already a lot better, but there are some obvious short-comings. We’re considering all query terms to be of equivalent value when assessing the relevancy for the query. However, it’s likely that certain terms have very little to no discriminating power when determining relevancy; for example, a collection with lots of documents about beer would be expected to have the term “beer” appear often in almost every document (in fact, we’re already trying to address that by dropping the 25 most common English words from the index). Searching for the word “beer” in such a case would essentially do another random sort.

In order to address that, we’ll add another component to our scoring algorithm that will reduce the contribution of terms that occur very often in the index to the final score. We could use the collection frequency of a term (i.e. how often does this term occur across all documents), but in practice the document frequency is used instead (i.e. how many documents in the index contain this term). We’re trying to rank documents after all, so it makes sense to have a document level statistic.

We’ll compute the inverse document frequency for a term by dividing the number of documents (N) in the index by the amount of documents that contain the term, and take a logarithm of that.

We’ll then simply multiple the term frequency with the inverse document frequency during our ranking, so matches on terms that are rare in the corpus will contribute more to the relevancy score5. We can easily compute the inverse document frequency from the data available in our index:

# index.py

import math

def document_frequency(self, token):

return len(self.index.get(token, set()))

def inverse_document_frequency(self, token):

# Manning, Hinrich and Schütze use log10, so we do too, even though it

# doesn't really matter which log we use anyway

# https://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/htmledition/inverse-document-frequency-1.html

return math.log10(len(self.documents) / self.document_frequency(token))

def rank(self, analyzed_query, documents):

results = []

if not documents:

return results

for document in documents:

score = 0.0

for token in analyzed_query:

tf = document.term_frequency(token)

idf = self.inverse_document_frequency(token)

score += tf * idf

results.append((document, score))

return sorted(results, key=lambda doc: doc[1], reverse=True)

Future Work™

And that’s a basic search engine in just a few lines of Python code! You can find all the code on Github, and I’ve provided a utility function that will download the Wikipedia abstracts and build an index. Install the requirements, run it in your Python console of choice and have fun messing with the data structures and searching.

Now, obviously this is a project to illustrate the concepts of search and how it can be so fast (even with ranking, I can search and rank 6.27m documents on my laptop with a “slow” language like Python) and not production grade software. It runs entirely in memory on my laptop, whereas libraries like Lucene utilize hyper-efficient data structures and even optimize disk seeks, and software like Elasticsearch and Solr scale Lucene to hundreds if not thousands of machines.

That doesn’t mean that we can’t think about fun expansions on this basic functionality though; for example, we assume that every field in the document has the same contribution to relevancy, whereas a query term match in the title should probably be weighted more strongly than a match in the description. Another fun project could be to expand the query parsing; there’s no reason why either all or just one term need to match. Why not exclude certain terms, or do AND and OR between individual terms? Can we persist the index to disk and make it scale beyond the confines of my laptop RAM?

An abstract is generally the first paragraph or the first couple of sentences of a Wikipedia article. The entire dataset is currently about ±796mb of gzipped XML. There’s smaller dumps with a subset of articles available if you want to experiment and mess with the code yourself; parsing XML and indexing will take a while, and require a substantial amount of memory. ↩︎

We’re going to have the entire dataset and index in memory as well, so we may as well skip keeping the raw data in memory. ↩︎

Whether or not stemming is a good idea is subject of debate. It will decrease the total size of your index (ie fewer unique words), but stemming is based on heuristics; we’re throwing away information that could very well be valuable. For example, think about the words

university,universal,universities, anduniversethat are stemmed tounivers. We are losing the ability to distinguish between the meaning of these words, which would negatively impact relevance. For a more detailed article about stemming (and lemmatization), read this excellent article. ↩︎We obviously just use our laptop’s RAM for this, but it’s a pretty common practice to not store your actual data in the index. Elasticsearch stores it’s data as plain old JSON on disk, and only stores indexed data in Lucene (the underlying search and indexing library) itself, and many other search engines will simply return an ordered list of document IDs which are then used to retrieve the data to display to users from a database or other service. This is especially relevant for large corpora, where doing a full reindex of all your data is expensive, and you generally only want to store data relevant to relevancy in your search engine (and not attributes that are only relevant for presentation purposes). ↩︎

For a more in-depth post about the algorithm, I recommend reading https://monkeylearn.com/blog/what-is-tf-idf/ and https://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/htmledition/term-frequency-and-weighting-1.html ↩︎